Schools are often judged by their exam results and it is undoubtedly important that young people gain the best qualifications they can to achieve future goals. But as Tania Clarke asks in her recent blog, what is the purpose of education? If it is to nurture young people to develop their potential holistically and prepare them to be productive citizens, then you could argue that a focus on academic qualifications alone is insufficient.

The World Health Organization (2005) has described mental health as a ‘state of wellbeing in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’. Therefore, if we want students to develop into productive citizens, they not only need academic credentials but also good future mental health and wellbeing. This is because wellbeing is not just about feeling well (hedonic wellbeing) but also functioning well (eudaimonic wellbeing – see Deci & Ryan, 2008, for further discussion of this distinction).

Large international surveys of young people’s wellbeing, however, make for sobering reading. For instance the 2018 PISA asked 15 year-olds about their satisfaction with life, how often they felt happy, and sad, and whether they felt a sense of meaning and purpose in life. An analysis of data from 24 European countries in this survey shows that less than half of those surveyed in each country had decent levels of wellbeing (scoring higher than the scale midpoint) on all of these aspects, with around 10 per cent expressing low levels of wellbeing on at least three of the four measures.

Furthermore, there is growing evidence that wellbeing and learning are inextricably linked. Recent research has shown, for instance, that better wellbeing is associated with more adaptive forms of motivation (wanting to learn and progress rather than focusing on performance relative to others or avoiding learning situations, see Wormington & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2017). Wellbeing is also linked to engagement. For example, an influential and substantial annual survey of young people’s wellbeing in the UK revealed those with lower levels of wellbeing were more likely to truant.

There is also evidence, perhaps not surprisingly, that wellbeing is linked to academic performance. Studies in the UK and USA among others have demonstrated not only a correlation between wellbeing and performance assessed at the same point of time for different age groups (children aged 10 up to 16 years of age), but also a link between wellbeing and performance when performance is assessed two years later (Gutman & Vorhaus, 2012; Suldo, Thalji, & Ferron, 2011).

So, there is no doubt that if we want effective and successful learners who will make positive contributions to society, we need to attend to young people’s wellbeing.

Looking after young people’s wellbeing and looking after staff wellbeing

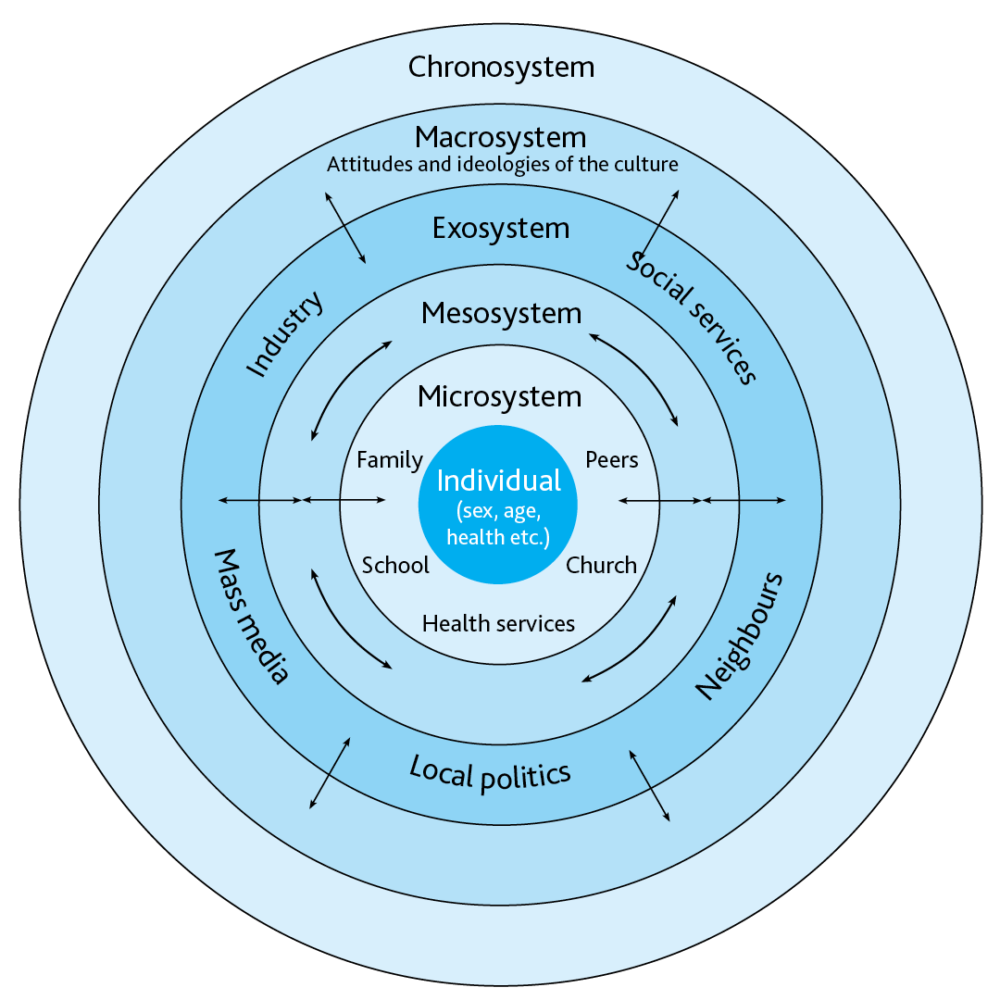

It is important to recognise that young people’s learning is not happening in a vacuum. Formal learning happens in classrooms facilitated by often very overworked staff, who themselves are in schools run by overworked senior leaders. In other words, there is an educational ecosystem. Bronfenbrenner (2005), in talking about human development, puts the individual at the heart of his ecological systems theory, that describes the interacting systems within which we exist in society. So, for example, a student is learning within the microsystem of a classroom interacting with staff and students. In turn this microsystem is nesting within and interacting with other systems outside the classroom – such as the family and local community, government policy and societal beliefs. All these systems evolve and change with time and what happens in one part of the ecosystem affects the rest of it, ultimately impacting the learner. A consequence of this, as a recent study has demonstrated (Harding et al., 2019), is that teacher wellbeing is very much linked to student wellbeing.

It also follows from the above, that to improve young people’s wellbeing, there is a need to think about not just the individual learner but to consider the educational ecosystem the learner is within. While as staff and senior school leaders we may not be able to directly influence government policy on education, or broader public beliefs in society around education and wellbeing, we can look at those aspects of the ecosystem within our remit. We need to consider whether our school policies and practices are doing all they can to support all of those within that system, in other words a whole-school approach is needed. Ultimately staff and student wellbeing shouldn’t be thought of as an additional thing to deal with – it is an inextricable part of the educational system. If policies and practices are congruent with staff and student wellbeing, students will be better learners.

How can schools establish policies and programmes to support everyone’s wellbeing?

It might be daunting for a senior leader to contemplate making ecosystem change to support wellbeing. Fortunately, there is useful guidance available. The World Health Organization, based on its definition of health as encompassing not just physical but also mental and social wellbeing, launched its Health Promoting (HP) Schools initiative as long ago as 1995. HP schools are underpinned by the values of equity, sustainability, inclusion, empowerment, and democracy and take a whole-school evidence-based approach.

As with any form of change, becoming a HP school needs careful management and planning through visioning, communication, and empowerment (Kotter, 1996), engaging everyone in the community. Usefully, the Schools for Health in Europe network produces resources to support schools endeavouring to become HP schools, including a detailed school manual outlining a five-stage process with a raft of planning and evaluation tools.

Getting started

It goes without saying that the starting point must be an understanding of pertinent wellbeing issues in your school context. There needs to be an open discussion involving all stakeholders (staff, students, parents, and other professionals and community groups linked to the school) not only to put the issue of wellbeing on the agenda, but also to find out what the perceived issues are and what the priorities should be.

This is likely to involve setting up an initial working group, actively and visibly supported by senior leaders, with members being given time and resources for the role. Involving students is crucial as research has shown that what adults think might be a concern for young people, may not be considered a concern by young people themselves, especially in relation to matters of wellbeing (Fattore, Mason, & Watson, 2016). It can be helpful to survey young people (and staff) about their wellbeing using a recognised tool. For instance, the ‘what I feel about school’ tool validated with children aged 7-16 years captures hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing (McLellan & Steward, 2015), whilst WEMWBS has been widely used with older adolescents and adults.

This working group will need to empower themselves through reading up on wellbeing to understand how it has been conceptualised. Cambridge International’s Education Brief on Wellbeing provides a good starting point.

Classroom approaches

Although it is important to identify priorities and develop a whole-school plan involving policies and procedures, ultimately teachers will need to implement strategies in their own classrooms. Wellbeing theories and research evidence suggest that wellbeing is contingent on a number of key aspects that include:

- a sense of meaning and purpose, self-acceptance, and growth

- autonomy and choices in learning

- the development of mastery and skills through appropriate challenge, resulting in a strong sense of self-efficacy

- positive relationships not only between student and teachers but with peers and others in school, strengthening a sense of belonging to school.

Strategies that promote some or all of the above are likely to foster wellbeing. Evidence is growing that mindfulness and yoga are useful practices, as well as keeping gratitude diaries and practising kindness as these promote meaning and purpose as well as self-acceptance. Creative and arts-based approaches have been particularly shown to support wellbeing through satisfying needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

The Teachappy website provides lots of useful and evidence-based resources including classroom strategies, which although designed for primary schools are easily transferable to a secondary contexts. For instance, actively encouraging students to reframe experiences to focus on what went well at the end of a lesson, rather than what didn’t work, will promote a sense of mastery, while a ‘tribal classroom’ engendering a sense of team will promote belonging. In a similar vein, Action for Happiness puts forward ‘10 (evidence-based) keys to happier living’ with lots of interesting and adaptable suggestions for how to enact these.

In the end, teachers themselves are best placed to adapt some or all of these suggestions to fit their context once they understand what they are trying to achieve. Empowerment is the key!

Resources

My keynote presentation at the Cambridge Schools Conference Online June 2021: ‘Supporting wellbeing in school – enabling young people to fulfil their potential’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u2JYeDjZKqU&list=PLi4xGU_d7k_Iw6pW5PW8GnauMhqRU2sjp&index=3

Education Brief on Learner Wellbeing https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/612684-learner-wellbeing.pdf

My wellbeing scale https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0305764X.2014.889659

Faculty of Education Wellbeing and Inclusion SIG Blog https://cambridgewellbeingandinclusion.wordpress.com/blog-2/

BERA Mental Health & Wellbeing SIG https://www.bera.ac.uk/community/mental-health-wellbeing-and-education – see blog collection https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/bera-bites-issue-6-researching-education-mental-health-from-where-are-we-now-to-what-next

www.teachappy.co.uk classroom resources

www.actionforhappiness.org more targeted at adults but adaptable for students

References

Bronfenbrenner. (2005). Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and well-being: An Introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1-11.

Fattore, T., Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2016). Children’s Understandings of Well-being: Towards a Child Standpoint. New York: Springer.

Gutman, L. M., & Vorhaus, J. (2012). The Impact of Pupil Behaviour and Wellbeing on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved from London:

Harding, S., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., Tilling, K., . . . Kidger, J. (2019). Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 180-187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

McLellan, R., & Steward, S. (2015). Measuring Student Wellbeing in the School Context. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(3), 307-332. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2014.889659

Suldo, S. M., Thalji, A., & Ferron, J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 17-30. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.536774

Wormington, S. V., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2017). A New Look at Multiple Goal Pursuit: the Promise of a Person-Centered Approach. Educational Psychology Review, 29(3), 407-445. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9358-2