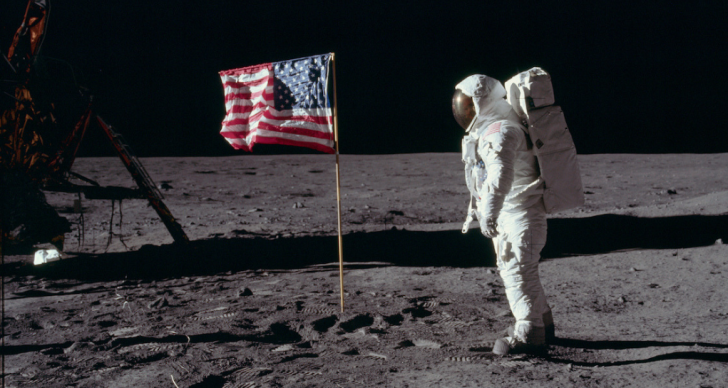

On 20 July 2019, we celebrate half a century since the first lunar landing.

I grew up fascinated by space and remain so, long into adulthood. While most of us have looked up at the sky and the stars, only a few have been lucky enough to view the Earth from afar. A few months prior to those first famous lunar footsteps, the crew of Apollo 8 became the first to orbit the Moon, and took the photo that has become known as ‘Earthrise’.

Kevin Fong, a former NASA scientist and presenter of the ‘13 minutes to the Moon’ podcast, has described what this image defines:

“It shows our Earth as a brilliant but small, blue, fragile marble, alone in the vastness of space. It changed the way we saw our home forever, and helped us understand our role as custodians of this planet.”

Astronauts since then, such as the Canadian, Chris Hadfield, who wrote An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth (2013), have been deeply affected by what they have seen:

“Space travel has made me feel I have a personal obligation to be a good steward of our planet and educate others about what’s happening to it.”

As we gaze in wonder at the Moon 50 years on and imagine how it felt to be in Neil Armstrong or Buzz Aldrin, it is a good moment to inspire our children about all that is remarkable about being here on Earth.

Leave no child inside

The urgent need to address climate change and environmental concerns is today at the top of the political and social agenda.

In recent months, the Swedish schoolgirl, Greta Thunberg, has inspired teenagers around the world to strike and protest against climate change. Yet fewer children than ever are in fact spending time in nature and only experience it second-hand. According to a 2016 survey, three quarters of children in the UK spend less time outside than prison inmates. This trend isn’t new – a University of Maryland study found that the proportion of 9-12-year-olds who spent time in such activities as hiking, walking, fishing and gardening declined by 50% between 1997 and 2003.

As Richard Louv writes in Last Child in the Woods (2005), “Within the space of a few decades, the way children understand and experience nature has changed radically. Today, kids are aware of the global threats to the environment – but their physical contact, their intimacy with nature, is fading.”

This is particularly stark in the light of increasing scientific evidence indicating that direct exposure to nature is essential for physical and emotional health. New studies suggest that simply being outside may reduce the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and that it can improve children’s cognitive abilities and resistance to negative stresses and depression.

‘Nature smart’

As educators and parents, it is important that we are aware of the benefits to children of being close to nature, and can spot the signs of children who are ‘nature smart’.

Professor Leslie Owen Wilson, from the University of Wisconsin School of

Education (quoted in Louv, pp 73-4), has described typical traits of ‘nature

smart’ children. They:

- have keen sensory skills, including sight, sound, taste, smell and touch;

- readily use heightened sensory skills to notice and categorise things from the natural world;

- like to be outside, or like outside activities like gardening, nature walks or field trips geared towards observing nature or natural phenomena;

- easily notice patterns from their surroundings – like differences, similarities, anomalies;

- are interested in and care about animals or plants;

- notice things in the environment others often miss;

- create, keep, or have collections, scrapbooks, logs, or journals about natural objects – these may include written observations, drawing, pictures and photographs, or specimens;

- are very interested, from an early age, in television shows, videos, books, or objects from or about nature, science or animals;

- show heightened awareness of and concern for the environment and/or endangered species;

- easily learn characteristics, names, categorisations, and data about objects or species found in the natural world.

These are 10 characteristics we could all aspire to have. Louv at the end of his book sets out a Field Guide of “100 Actions We Can Take” to be more nature-aware, including activities for children and families, suggestions for transforming our communities, and ways to promote reform.

The world is a stage

Command Module Pilot Jim Lovell, who was a member of the Apollo 8 crew, spoke about how his world “suddenly expanded to infinity” when seeing the Earth at a distance of 240,000 miles:

“I began to question my own existence. How do I fit in to what I see? Then I remembered a saying I often heard: ‘I hope I go to Heaven when I die.’ I suddenly realised that I went to Heaven when I was born! I arrived on a planet with the proper mass to have the gravity to contain water and an atmosphere, the essentials for life. I arrived on a planet orbiting a star at just the right distance to absorb that star’s energy—energy that caused life to evolve in the beginning. In my mind the answer was clear. God gave mankind a stage upon which to perform. How the play ends, is up to us.”

We can continue to explore our galaxy and inspire children to be part of future space programmes, but we should also encourage them to play a part in shaping the future of their own natural world. Let’s look to the Moon, but let’s not forget to look back.

References and further reading

13 Minutes to the Moon (BBC World Service podcast presented by Kevin Fong)

National Air and Space Museum (website)

Hadfield, C., 2013. An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth. Canada: Random House.

Louv, R., 2005. Last Child in the Woods. New York: Algonquin Books.