Helen Rees-Bidder is the author of ‘Approaches to Learning and Teaching First Language English’.

What is ‘oracy’?

The term ‘oracy’ was coined in the 1960s by Andrew Wilkinson. His notion was that oracy should be given equal status to numeracy and literacy in school curriculums, yet over 50 years later that does not seem to be the case in the majority of schools.

In schools where students are educated in English, but another language is spoken at home, leading learning through oracy is even more important.

Language needs to be acquired naturally to build up natural fluency and rather than learning new vocabulary for use in written responses, students should be offered opportunities to build content vocabulary through discussion and oral presentations. If a student’s spoken English improves, developments in their written English will follow.

Teacher talk

As Head of a Performance Arts Faculty, I became aware of how many senior teaching staff disliked doing formal presentations. Often the greatest fear of a newly appointed Head of Year was taking assemblies.

I also noticed that in meetings colleagues often avoided opportunities to voice their opinions or make contributions, yet after the meetings would have plenty to say about what had been discussed as we walked back to our cars.

It seemed odd that people who had chosen a profession which is so reliant on effective speaking were so uncomfortable when using their oracy skills outside the safety zone of their own classrooms.

Confidently speaking in public, whether as a presenter or in a meeting, is something that I have always taken for granted, presumably linked to my love of acting as a school and university student.

It was really through extra-curricular drama provision that I learnt to use my voice effectively, work collaboratively and develop my confidence.

It was only when I began to teach Drama in a very academic school that I realised that parents often encouraged (or sometimes forced) their son or daughter to take IGCSE Drama or Speech & Drama lessons to build up their confidence, presentational skills and articulacy rather than because they enjoyed acting.

It then struck me that it shouldn’t be dependent on a Drama department to teach and develop oracy skills, which are so crucial in all aspects of 21st-century life. Children need to be confident and effective communicators to become empowered young citizens.

In the world of work, how successfully we communicate is likely to be the primary judgement of our effectiveness whatever field we are in.

Surely it is the job of every classroom teacher, whatever the subject, to develop oracy skills?

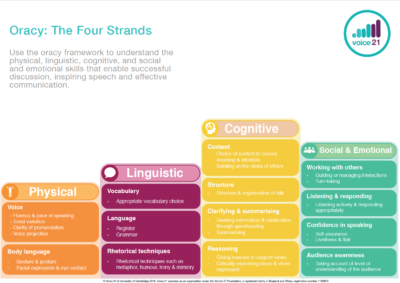

Voice 21, a UK campaign group which promotes oracy in the classroom, have produced an oracy framework which defines the four strands of skills which enable effective talk:

This framework is not subject-specific and stresses that oracy should be developed right across the curriculum rather than be left as the preserve of English classrooms.

So how can teachers develop oracy skills in every student?

- Change your classroom culture to ensure that every lesson is deliberately structured to include oracy and every student is expected to contribute

- Develop the language of discussion in your classes by exploring the way that oral language is structured and teaching students the tools of effective talk

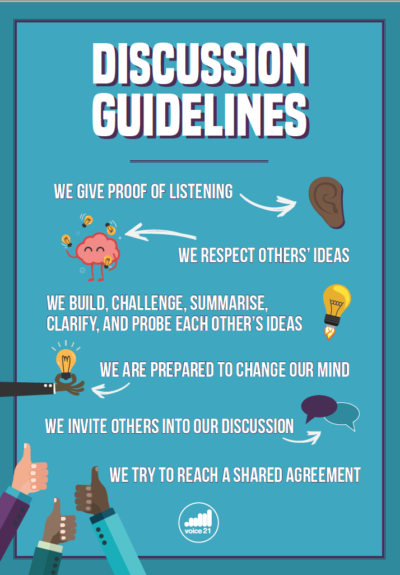

- Establish rules to ensure that discussions are conducted with clear guidelines and enable every student to take part. See below for an example of discussion guidelines drawn up by Voice 21

- Model effective talk through your own use of tone, vocabulary and content, as well as following the rules yourself

- Carefully scaffold and guide discussions through careful use of different types of questions

- Think carefully about how different types of groupings work for different activities

- Use talk to formatively assess knowledge and understanding

Demonstrating communication skills

My daughter recently got her first job. She was nervous about applying for one because she had chosen Dance as her degree subject. She was worried that her applications for jobs in recruitment and marketing wouldn’t be successful because she hadn’t studied a more traditional ‘academic’ subject.

When she was offered a job, she was told that her communication skills were judged to be excellent and that she had shown real understanding of the importance of collaboration and flexible thinking in her interviews (telephone, then video, then face-to-face).

These are all skills which we have to demonstrate every time we attend an interview or assessment day and getting to the second round is usually dependent on demonstrating them successfully. These are skills which can only be developed through talk!

Further reading

Read more articles from the authors in the ‘Approaches to Learning and Teaching’ series: